I Had That Dream Again Grampa

Towards the end of the Second World War, a immature adult female from Czechoslovakia fell in love with an Italian soldier on the island of Sicily. Helen and Alfonso were married in Catania, Alfonso's hometown, and it was in that location that Helen conceived a child – one of the millions whose lives began in the anarchy and displacement of state of war.

For reasons long since buried or forgotten, Helen left Sicily earlier the child was born. She travelled by transport to Syria, where she had a blood brother and where, in 1945, she gave birth to a babe boy. That boy never knew his begetter, never learned Italian, never gear up foot on Italian soil. But he was baptized with an Italian name – Giuseppe Camastra – and registered in Damascus as an Italian national.

Seventy years later, that thread of Italian ancestry became a lifeline for Giuseppe's children and grandchildren.

In the spring of 2011, as unrest spread across Syria, Giuseppe's son, Alberto, received a phone call from the Italian embassy: do you want to get out?

Every Italian in Syria got that telephone call. The Camastras were on the list because, decades subsequently his own male parent had left Sicily in utero, Alberto was withal listed equally an Italian national.

Syria, though, was the only country he'd ever known. Going to Italy meant becoming a refugee.

"I was afraid. I am 45 years old. I know no Italian. Where volition we live in Italy? Peradventure we terminate up in the street? For three years they chosen me, but I ever said 'No'."

Past the summer of 2014, though, the adding had inverse.

The shelling and gunfire were now so shut that Albertos' younger children were sleepless with fear. "My son was crying for three days. My married woman was frightened. So I said 'OK, I get'. Even if I cease up in the street, it'due south meliorate than this."

They were the last Italians to leave the land.

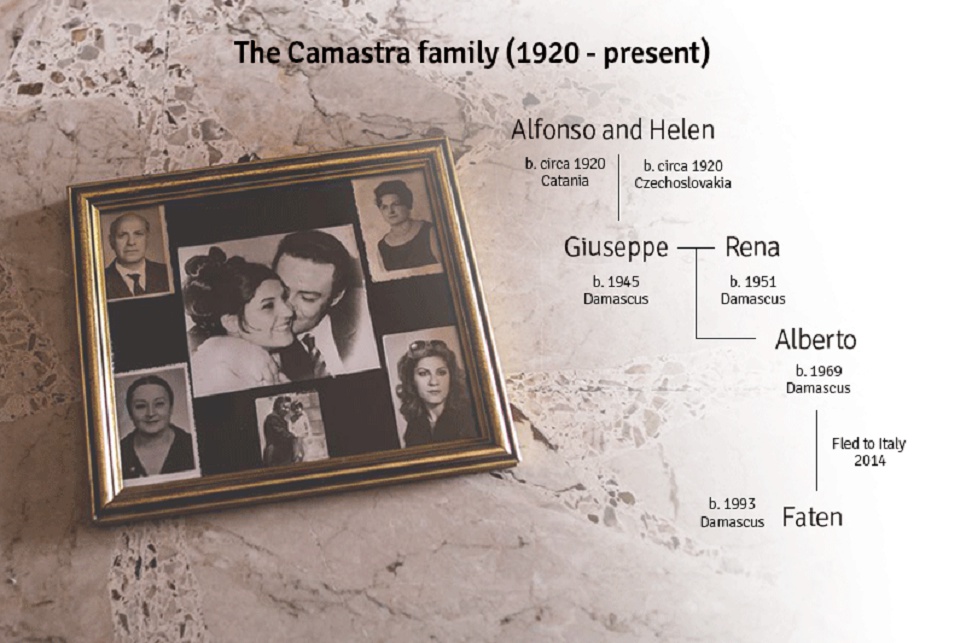

The Camastra family unit tree from Sicily to Syria and back over again. © UNHCR

"I was afraid. I am 45 years old. I know no Italian. Where will we alive in Italy? Mayhap nosotros end up in the street?"

About a twelvemonth after the Camastras left, I met Alberto at a street café in Catania. The strain of the final few years was written on his face.

In Syria, he had sold what he could and brought his wife, mother and four children by taxi to Beirut and so by aeroplane to Rome. The other Syrian refugees in Italy were all heading north towards Germany, where hundreds of thousands of refugee applications are accepted every year, but Alberto took the train due south towards Sicily. He was going dorsum to the metropolis in which his begetter had been conceived.

Catania may take been his grandfather'southward hometown, but Alberto had no other connection to the place. In Syria, he had been the breadwinner. Here, without a word of the language, he struggled to find a safety place for the kids to sleep. "If I am alone," he told me, "I can slumber anywhere, even in the park. But with the children . . . "

For a few nights they stayed in a cheap hotel, and then in an unfurnished room without water or electricity. Finally, Alberto borrowed what he could from his wife'south family in Syria and put down a year's rent on an apartment. Not long after that, he had a middle set on.

Alberto'due south hospitality, though, had survived the pressures of war, and he invited me to meet his family at their home on the western edge of the city.

Alberto's female parent, Rena, answered the door and, surrounded by excited grandchildren, showed me round. The apartment was in a tired-looking 1960s cake of flats, but the Camastras had painted the walls pinkish and polished the floor tiles to a loftier gleam. On the wall of the living room hung a frame of photographs taken in Damascus 50 or 60 years agone.

Helen was in that location, the Czech girl whose Sicilian wartime romance had brought this branch of the Camastra family into being. So were Rena's own parents, Vasili and Victoria, who had come from Greece and Lebanon and who had always felt part of Syrian arab republic'southward religious and ethnic mosaic. These people had known the Mediterranean world every bit a place of fluidity and movement, of mixed marriages and mixed faiths. "When I was immature," Rena told me now, "there was not a big difference between Europe and Syria."

"When I was immature, there was not a big divergence betwixt Europe and Syria."

If Rena carries the family's memories, information technology is her oldest granddaughter, Faten, who carries its hopes. In Damascus, she had almost completed a law degree before the war forced her to abandon her studies. Already fluent in English language and Arabic, she is soaking upwards Italian from the streets and planning to start university again. At the same time, she is working as a nanny for an Italian family unit, bringing in the money that is soon due on the rent.

I asked her how it feels to be back in the city that her great-grandmother left all those years ago. "I feel grateful for this big circle that my family has travelled," she said. "I feel grateful that I can speak Standard arabic, that I tin understand the music and poetry of the Standard arabic language. This whole long story, all these different countries, it made me a more complex person."

Share on Facebook Share on Twitter

preussfornevenithe.blogspot.com

Source: https://www.unhcr.org/news/stories/2015/8/56ec1ea51f/sicily-to-syria-and-back-again.html

0 Response to "I Had That Dream Again Grampa"

Post a Comment